Beneath St Michael’s lie the remains of the Roman Basilica – the great Forum built in the first century AD. Here (or nearby) in AD 179, King Lucius is said to have established the first Christian place of worship in London.

The church of St. Michael’s is known to have been in existence before the Norman Conquest, for it is recorded that in 1055 Alnothus the priest gave it to the abbot of Evesham. In 1503 the patronage was transferred to the Drapers’ Company, which still has the gift of the living.

Robert Fabyan, the author of The New Chronicles of England and France, was buried at St. Michael’s in 1513; and King Henry VIII’s physician, Robert Yaxley, was buried here in 1540.

In 1716, the poet Thomas Gray, famous for his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, was born in a milliner’s shop adjacent to St. Michael’s and was baptised in the church. Two hundred years later, Martin Neary, who became Master of the Music at Westminster Abbey, was baptised in the same font, which dates from 1672.

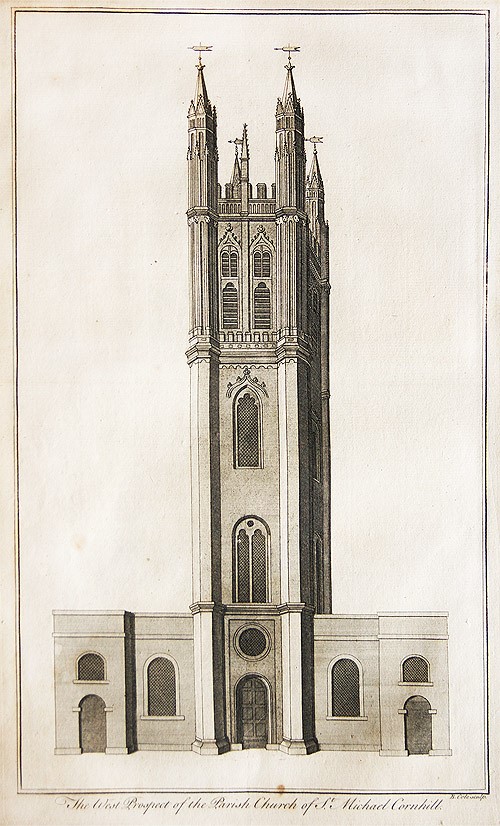

The church, with the exception of the tower, was completely destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. It was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren between 1669 and 1672. The interior, with its majestic Tuscan columns, was beautified and repaired in 1701 and again in 1790. Pre-Victorian features that remain today include 17th paintings of Moses and Aaron incorporated into the reredos, as well as a wooden sculpture of ‘Pelican in her Piety’ dating from 1775. The vestry retains its 17th century panelling, with a fine carved overmantel. The commanding tower was rebuilt in the ‘Gothick’ style between 1718 and 1722, the work being commenced by Wren and completed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. It houses a peal of 12 bells, including some of the originals cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

The interior of the church was extensively remodelled in the High Victorian manner by Sir George Gilbert Scott between 1857 and 1860. Scott recalled that he ‘attempted by the use of early Basilican style to give a tone to the existing classic architecture’. As part of this scheme of reordering, the eminent woodcarver William Gibbs Rogers carved new pews and a pulpit and lectern (which earned him a prize in the Great Exhibition of 1851). In addition, an ensemble of stained glass was made by the firm Clayton & Bell and a new porch, with a tympanum sculpture of St. Michael by John Birnie Philip, was added.

In 1906, the parishes of St. Peter le Poer and St. Benet Fink were united to St. Michael’s upon the demolition of St Peter’s. (St Benet’s had been demolished in 1846.) Hence the practice of appointing seven churchwardens, three for St Michael’s and two for each of the other parishes. The Church was fortunate to escape serious damage in the Second World War. The interior was restored in 1960, with the roofs and the nave of the tower being renewed in 1975.